The Pingyao Tea House Theater is, as its name says, a Tea House; ancient tea houses in China were much more than their name implies to us in these days: they were hostels (special ones, not just anyone could stay there, only people from a specific region or group), party saloons, theaters, a kind of cabaret, restaurants and, of course, places where you could drink some tea. Historians say that performances in there were done in the middle of a unimaginable chaos ( it seems a common characteristic of theaters around the world in the past): people were eating, drinking, having fun, playing all kinds of table games, shouting, laughing, walking, and not always with an interest in the spectacle being performed at the moment. You can observe in detail the picture above, a Tea House performance during the last years of Qing Dinasty, as a very good example of what I am talking about.

It seems that temples and palaces were similar, a theater performance was part of a huge movement around festivities or court parties. None of these conducts seem to have bothered the artists, they were used to it.

It seems that temples and palaces were similar, a theater performance was part of a huge movement around festivities or court parties. None of these conducts seem to have bothered the artists, they were used to it.

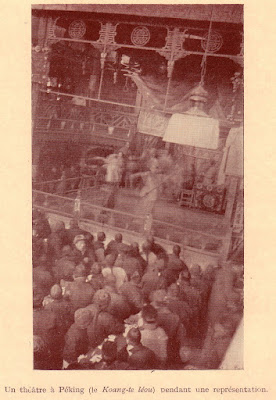

The next photographs show not a tea house but a theatre (Kuang-te lou) in central Beijing at the beginning of 20th Century (1), you can even see tables and how, during the performance, people are served food and drinks.

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)Today, a common Western spectator still perceives as different how a Chinese spectator reacts to any spectacle and how they behave during a performance, but the change with how it used to be in the past is remarkable. Even today in the VIP section you can be served tea and cookies, with waiters walking from one seat to another during the performance, people receiving phone-calls and people talking in a normal level of voice, yet the theatre staff always ask for silence and for people to turn off their mobiles.

So, that code of conduct during a spectacle is threatened with its end, except for one special place, tea houses for tourists.

Now we can come back to our post subject. The Pingyao Tea House Theater is a theater which opens for tourists, for groups and more groups of hungry and energetic Chinese tourists. They come to this place after a long day of walking and visiting temples, museums, shops around the ancient city of Pingyao, and they want to finish the day with a meal (the most important experience for any Chinese), a laugh and enjoying a very traditional show. That is what I called an anthropological experience: a bit of that ambiance and public conduct under which performances were done in the past. A game, of course, but a very interesting one.

It is kind of difficult, due to the noise during Chinese opera performances, to differentiate the spectators’ noise, but you can taste a little bit of it in the next videos:

Video: spectators getting into Prince Gong Residence Tea House Theatre

And the last one, in the turist village of Wuzhen, a Shadow Puppet Theatre spectacle; spectators were children but that afternoon none of their teachers asked for silence... (if you listen carefully you will noticed voices of adults as well)

I remember some of the words my teachers tried to define (in their ignorance of it) the Oriental theatre: a theatre where dance, acting, singing, acrobacy, secular parties and religion were mixed... and its spectator behaved in accord to it.

(1) "Théâtre et Music Modernes en Chine" by George Souliè de Morant. Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner. Paris, 1926.

(2) "Salesman in Beijing" by Arthur Miller. London, 1984.

No comments:

Post a Comment