After two years of writing this Blog I only can say:

Thank you to all of you!

I wish you a very happy new year 2009!

Gustavo Thomas

Beijing, China

December 30th, 2008.

Monday, December 29, 2008

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

Pingyao Tea House Theater (3): Three scenes of Shanxi Opera

Following my series of "Pingyao Tea House Theater" (1), this last part presents three scenes performed during the same spectacle for tourists I have been talking in part 1: one acrobatic scene, one comic scene and one quick-changing masks scene.

Even the spectacle that night were not only of Shanxi Opera it was an unique opportunity to see a company specialized on it playing some characteristic scenes of that kind of Chinese theatre. Shanxi Opera performances are not as easy to find than Peking Opera performances; there are no much companies and their seasons are rare, usually they give some isolated performances in very special occasions.

Video 1: an acrobatic scene of Shanxi opera

Shanxi Opera: Acrobatic Scene at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

The acrobatic scene did not show to me anything special, being very similar to other kind of Chinese operas I have seen before, I only corroborated my appreciation of those amazing actors-acrobats always working to perfection (even in spectacles like this).Shanxi Opera: Acrobatic Scene at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

Video 2: A comic scene of Shanxi opera

Shanxi Opera: Comic Scene at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

The Comic scene was an interesting surprise; it was the first time I heard singing like that, not only comically but with a very special use of the rhythm. This Shanxi Opera song showed to me a very fresh way to sing in traditional Chinese theatre, codification was still there but the difference with Peking Opera (the opera I have seen the most) seemed huge.Shanxi Opera: Comic Scene at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

Video 3: A quick-changing Mask scene of Shanxi opera.

Shanxi Opera Masks changes in Pingyao (2008) from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

Shanxi Opera Masks changes in Pingyao (2008)

Shanxi Opera Masks changes in Pingyao (2008) from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

Shanxi Opera Masks changes in Pingyao (2008)

I couldn't miss a quick-changing Mask scene; people from all over the world come to the South of China to see these actors doing that amazing switch of masks. It was a pity they did not do that inside a real opera scene, instead of it they performed those changes like an act of Magic. Not bad but it seemed to me more Las Vegas-kind spectacle than a Shanxi Opera one.

(1) "Pingyao Tea House Theater (1): Shanxi Opera Scenes Murals.", and

"Pingyao Tea House Theater (2): Seeing today Chinese spectators as an anthropological experience?"

Texts, photographs and videos in this Blog are all

author's property, except when marked. All rights reserved by Gustavo

Thomas. If you have any interest in using any text, photograph or video

from this Blog, for commercial use or not, please contact Gustavo Thomas

at gustavothomastheatre@gmail.com.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

北京龙在天皮影 Longzaitian, Chinese Shadow Puppet Theatre Company: "Tale of the goat and the wolf"

About a year ago the renovation of Qianmen street begun. In downtown Beijing, Qianmen was the main avenue that for centuries led the whole of the known world to the main gate (Qianmen means “front gate”) of the walls of the forbidden city.

After the fall of the millenary Chinese empire (at the beginning of the 20th century), the pre-communist years and the communist era itself, Qianmen street became just some old houses and buildings on the verge of collapse. Surrounded by one of the neighbourhoods (hutongs) of greatest commercial and cultural tradition, Qianmen remained important only due to its location, south of Tian’anmen Square.

After the fall of the millenary Chinese empire (at the beginning of the 20th century), the pre-communist years and the communist era itself, Qianmen street became just some old houses and buildings on the verge of collapse. Surrounded by one of the neighbourhoods (hutongs) of greatest commercial and cultural tradition, Qianmen remained important only due to its location, south of Tian’anmen Square.

After a year of works, Qianmen has been mostly renovated and, though there are tinges of aesthetic falsity (its central part was conceived as a thematic luxury mall, for example), the street looks like during the best years of the Qing dynasty. What’s most interesting in this important renovation is the rescue (at least façade-wise) of the most important buildings, of traditional shops and of a series of places where Beijing’s cultural life developed for hundreds of years. And so, walking on the street and its environs we can visit famous shops, traditional pharmacies, restaurants, cinemas (the first one of China, for example) and some theatres.

One of the theatres that has had more movement thanks to the street renovation (yet not its building, which still is to be renovated) is the one that belongs to the Longzaitian (or “Dragon in the Sky” in Chinese, 北京龙在天皮影) shadow puppet theatre company.

In one building the company houses three small theatre halls, some puppet-creation workshops, and a gallery-museum.

What I found most enjoyable during this visit was the possibility to (finally) watch and watch again shadow puppet performances in Beijing; it had always been hard for me to find an established place where shadow puppet performances took place regularly and by a stable company. Until then, I had only been able to see isolated performances by provincial groups or, in very special events, by pekinese groups.

Last October 12th (Sunday) 2008 I saw two performances with two of the company’s groups: “The story of the goat and the wolf”, addressed to children, and “The three defeats of the skeleton-demon”, a traditional performance based on a story taken from “Journey to the West”, one of the greatest pieces of Chinese fantasy literature.

At that point in my stay in China, and having seen dozens of performances by different groups and companies, I think I was able to better appreciate the work needed for a performance; I recognised the use of a more “flexible” kind of puppet, and a clearer way of telling stories for the modern spectator. I still can’t recognise the differences in their techniques for handling the puppets, but it is true that, unlike the groups from the Chinese provinces, the shadow puppet groups from Beijing are (as is the case with traditional opera) oriented more to real entertainment and they manage to keep the attention of the modern spectator; they have no qualms in transforming traditional plays.

The company is made up of two groups, one for children and one for traditional performances.

I’d like to mention two curious facts. The puppets for “The tale of the goat and the wolf” are handled by puppeteers with dwarfism (the company advertises them as such; a possible translation of the Chinese words used could be “pocket puppeteers”), and they don’t sing nor play instruments (as is usual in Chinese shadow puppet groups), but instead make use of “playback”.

I managed to record the whole of “The tale of the goat and the wolf”, which lasts about 13 minutes, but the traditional piece “The three defeats of the skeleton-demon”, which lasts longer (some 23 minutes) didn’t fit in the memory of my camera and therefore I couldn’t record all of it.

For now, I share “ The tale of the goat and the wolf” and I promise to share a traditional play in a next posting.

Part 1: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jyWZOAeoeGo

Part 2: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7F1M4h8bI_E

Part 2: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7F1M4h8bI_E

Complete video in Ipernity:

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

三枝橘制作 Théâtre des trois oranges: A rehearsal of Luxun's "Ye Cao" 野草

Here some images of one rehearsal of Ye Cao 野草 (Wild Grass), last Théâtre des Trois Oranges's production in Beijing, China. October, 2008. I was invited by Xavier Froment and it was interesting to see this production since rehearsals and then having a point of reference to watch the performance.

I had also the opportunity to see (for first time) Kang Luqi working. He is one of Froment's titular actors. During this rehearsal I saw him as any other actor repeating movements, recalling texts, etc. But days later watching him on stage, in performance, things were different, in front of my eyes he became a very strong image of a good actor, surprisingly finding a place in my spectator's memory.

I had also the opportunity to see (for first time) Kang Luqi working. He is one of Froment's titular actors. During this rehearsal I saw him as any other actor repeating movements, recalling texts, etc. But days later watching him on stage, in performance, things were different, in front of my eyes he became a very strong image of a good actor, surprisingly finding a place in my spectator's memory.

There will be a special post for the performance.

Video of "Ye Cao" rehearsal (Théâtre des Trois Oranges)

Photographs of "Ye Cao" rehearsal (Théâtre des Trois Oranges)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Photographs of "Ye Cao" rehearsal (Théâtre des Trois Oranges)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008) Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008) Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008) Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008) Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)

Xavier Froment and Kang Luqi in rehearsal (Théatre des Trois Oranges. Beijing. October, 2008)Wednesday, December 3, 2008

Pingyao Tea House Theater (2): Seeing today Chinese spectators as an anthropological experience?

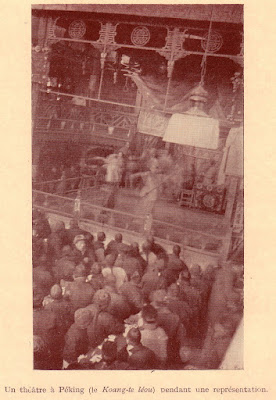

The Pingyao Tea House Theater is, as its name says, a Tea House; ancient tea houses in China were much more than their name implies to us in these days: they were hostels (special ones, not just anyone could stay there, only people from a specific region or group), party saloons, theaters, a kind of cabaret, restaurants and, of course, places where you could drink some tea. Historians say that performances in there were done in the middle of a unimaginable chaos ( it seems a common characteristic of theaters around the world in the past): people were eating, drinking, having fun, playing all kinds of table games, shouting, laughing, walking, and not always with an interest in the spectacle being performed at the moment. You can observe in detail the picture above, a Tea House performance during the last years of Qing Dinasty, as a very good example of what I am talking about.

It seems that temples and palaces were similar, a theater performance was part of a huge movement around festivities or court parties. None of these conducts seem to have bothered the artists, they were used to it.

It seems that temples and palaces were similar, a theater performance was part of a huge movement around festivities or court parties. None of these conducts seem to have bothered the artists, they were used to it.

The next photographs show not a tea house but a theatre (Kuang-te lou) in central Beijing at the beginning of 20th Century (1), you can even see tables and how, during the performance, people are served food and drinks.

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925) Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)

Kuang-te lou Theatre, Beijing (1925)Today, a common Western spectator still perceives as different how a Chinese spectator reacts to any spectacle and how they behave during a performance, but the change with how it used to be in the past is remarkable. Even today in the VIP section you can be served tea and cookies, with waiters walking from one seat to another during the performance, people receiving phone-calls and people talking in a normal level of voice, yet the theatre staff always ask for silence and for people to turn off their mobiles.

So, that code of conduct during a spectacle is threatened with its end, except for one special place, tea houses for tourists.

Now we can come back to our post subject. The Pingyao Tea House Theater is a theater which opens for tourists, for groups and more groups of hungry and energetic Chinese tourists. They come to this place after a long day of walking and visiting temples, museums, shops around the ancient city of Pingyao, and they want to finish the day with a meal (the most important experience for any Chinese), a laugh and enjoying a very traditional show. That is what I called an anthropological experience: a bit of that ambiance and public conduct under which performances were done in the past. A game, of course, but a very interesting one.

It is kind of difficult, due to the noise during Chinese opera performances, to differentiate the spectators’ noise, but you can taste a little bit of it in the next videos:

Video: spectators getting into Prince Gong Residence Tea House Theatre

And the last one, in the turist village of Wuzhen, a Shadow Puppet Theatre spectacle; spectators were children but that afternoon none of their teachers asked for silence... (if you listen carefully you will noticed voices of adults as well)

I remember some of the words my teachers tried to define (in their ignorance of it) the Oriental theatre: a theatre where dance, acting, singing, acrobacy, secular parties and religion were mixed... and its spectator behaved in accord to it.

(1) "Théâtre et Music Modernes en Chine" by George Souliè de Morant. Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner. Paris, 1926.

(2) "Salesman in Beijing" by Arthur Miller. London, 1984.

Saturday, November 29, 2008

A Strindberg portrait at Ibsen's studio

The fight between Realism and Supernaturalism (Symbolism) that becomes evident at the end of the 19th century in many aspects of art, though particularly in theatre, has an evident parallelism, I’m convinced, in the fight between their two major exponents in modern theatre: Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg. Their theatrical currents are an encounter between conscious and unconscious, between the idea of personality and the inner self or the unconscious.

Nevertheless, the personal relationship between Ibsen and Strindberg is somewhat unknown by the readers of either authors, and in turn is a curious chapter in the history of theatre and of art in general (1). Two geniuses who never met in person but who had an intimate and dramatic relationship. Two opposing visions of theatre, of literature and of the world they lived in, with just one point in common during Strindberg’s attempt, in his first years in his writing career, to imitate Ibsen’s work

Strindberg lived a real obsession about Ibsen’s work and person, he went from being, first, an emulator and admirer of the Norwegian writer, to becoming later one of his sharpest critics. His attacks were direct, continuous and went from deep analyses of the Ibsenian work to simple and plain offenses to his social behaviour.

Ibsen never understood those attacks, or he never wanted to keep an open (nor closed) fight with Strindberg; his standing in Europe’s intellectual society was, anyhow, much higher and, when it came to comparisons at the time, he was undoubtedly the winner; he didn’t need to write a single word against the work or person of Strindberg.

Nevertheless, that indifference to the Swedish writer’s attacks didn’t mean at all that Ibsen didn’t stop to contemplate the great man and artist that Strindberg was.

When Henrik Ibsen was in Stockholm, on April 13th 1898, celebrating his 70th birthday (yes, it wasn’t his birthplace, but the Swedish government offered homages in his honour), a Swedish journalist asked his opinion on Strindberg. Ibsen described the Swedish writer, 27 years younger, as “A great talent”, adding “I don’t know him personally - our paths have never crossed - but I’ve read his work with great interest. In fact, his last play, Inferno, has left a deep impression on me.” (2)

The impression that Strindberg caused on Ibsen was such that, years before that declaration, Ibsen had, in his own studio in Oslo, a portrait painting of the Swedish artist. He didn’t know him personally, but he was taken by his image, his personality and the strength of his literary work.

Nevertheless, the personal relationship between Ibsen and Strindberg is somewhat unknown by the readers of either authors, and in turn is a curious chapter in the history of theatre and of art in general (1). Two geniuses who never met in person but who had an intimate and dramatic relationship. Two opposing visions of theatre, of literature and of the world they lived in, with just one point in common during Strindberg’s attempt, in his first years in his writing career, to imitate Ibsen’s work

Strindberg lived a real obsession about Ibsen’s work and person, he went from being, first, an emulator and admirer of the Norwegian writer, to becoming later one of his sharpest critics. His attacks were direct, continuous and went from deep analyses of the Ibsenian work to simple and plain offenses to his social behaviour.

Ibsen never understood those attacks, or he never wanted to keep an open (nor closed) fight with Strindberg; his standing in Europe’s intellectual society was, anyhow, much higher and, when it came to comparisons at the time, he was undoubtedly the winner; he didn’t need to write a single word against the work or person of Strindberg.

Nevertheless, that indifference to the Swedish writer’s attacks didn’t mean at all that Ibsen didn’t stop to contemplate the great man and artist that Strindberg was.

When Henrik Ibsen was in Stockholm, on April 13th 1898, celebrating his 70th birthday (yes, it wasn’t his birthplace, but the Swedish government offered homages in his honour), a Swedish journalist asked his opinion on Strindberg. Ibsen described the Swedish writer, 27 years younger, as “A great talent”, adding “I don’t know him personally - our paths have never crossed - but I’ve read his work with great interest. In fact, his last play, Inferno, has left a deep impression on me.” (2)

The impression that Strindberg caused on Ibsen was such that, years before that declaration, Ibsen had, in his own studio in Oslo, a portrait painting of the Swedish artist. He didn’t know him personally, but he was taken by his image, his personality and the strength of his literary work.

In 1893, while he lived in Berlin, August Strindberg posed many times for the Norwegian painter Christian Krogh, who painted seven portraits of him; one of those paintings was acquired by Henrik Ibsen, according to himself, “for the, relatively speaking, ridiculous sum of 500 crowns.” Ibsen’s studio (and his whole apartment) is kept in the Ibsensmuseet (Ibsen's Museum) in Oslo (3), but Krogh’s painting is not there anymore, as it hangs at the Museum of Popular Art of Norway.

Ibsen saw in Strindberg a powerful figure, almost mythical; the portrait by Krogh not only was hanging in his studio, but had a primary place in it, exactly in front of his workplace. He used to say that he liked to look at it while he wrote, and that it seemed the man in the portrait would look straight at him like a “madman approaching him with demented eyes”. He particularly enjoyed looking at those “demonic eyes” and, at some point in his life, he commented “He is my mortal enemy; he must hang there and observe everything I write.” (4)

Ibsen’s quotations, from his own mouth, are manifestly clear, that strong impression can’t be concealed.

Ibsen’s personality, reserved as he was and profoundly correct (even during his most famous scandals) didn’t leave room to recognise in him his great personal fears, obsessions and passions, but he undoubtedly struggled with the forces that August Strindberg and his work represented; the hanging portrait in his studio is proof to the presence of the “other” in his creative life, of his struggle and, of course, of his admiration.

The theatre director August Lindberg, a friend of Strindberg’s, tells of how, when visiting Ibsen’s studio, Ibsen asked him if the portrait on his wall resembled the real Strindberg. Then, and without waiting for an answer, Ibsen got close to him and, almost whispering, maybe trying not be heard, he affirmed “A remarkable man!”.

(1) In a curious and interesting essay Barbara Lide, from the Technical University of Michigan exposes the “admiration-hate-fear” relationship between two of the greatest writers and dramaturgs of modern theatre, a strange relationship that has all the characteristics of the currents each of the belongs to in theatre.

(2) Most of my citations have been taken from the book “Henrik Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism” by Toril Moi (Oxford University Press. London, UK 2006), as well as from the article: “Strindberg’s Ibsen: Admired, emulated, scorned, and parodied” by Barbara Lide (Michigan Technological University which, in turn, is based on Strindberg’s basic biography by Meyer.

(3) The presence of Strindberg’s portrait by Krogh in Ibsen’s studio is known through direct citations from the Norwegian author, as well as from friends and acquaintances of his. The information was taken from Toril Moi’s book as well as from Barbara Lide’s essay.

Ibsen's studio. Ibsenmuseet, Oslo.

(4) One of Ibsen’s phrases (translated into English) that remain as his appreciation of the portrait is "Insanity Emergent".

Author's note: This is a personally revised translation (made by Tadeo Berjón) from my original post in Spanish..

Sunday, November 23, 2008

Pingyao Tea House Theater (1) : Shanxi Opera Scenes Murals

Pingayo Tea House Theater is a recent rebuilt building, it was constructed during Ming Dinasty (around 1700 AD) at the best moment of Pingyao City. It is called Tea house because remains on it that special character of the "Chinese cabaret place", a theater where is possible to see in one evening, drama, opera, acrobatics, singing, magic and clowns while a dinner, and tea of course, is served.

Its stage hosts one company of Shanxi Opera, a regional style of Chinese Traditional Theater, offering scenes from this kind of Opera to hungry groups of Chinese turists. (It will be the subject of other posts)

There are, inside the Tea House Theater complex, and surrounded by traditional gardens, one long wall with clay made murals, in high reliefs o "altorelieve", showing scenes from Shanxi opera plays. Even the artistic work is not fantastic it is an interesting experience.

The amount of artistic depictions of theater artists and scenes of plays in China is comparable to the amount of religious images in temples or political scenes in palaces, that is something I have never seen in other part of the world. The social importance of theater before the Communist era was really remarcable, and these murals are a prove of it.

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Texts, photographs and videos in this Blog are all author's property, except when marked. All rights reserved by Gustavo Thomas. If you have any interest in using any text, photograph or video from this Blog, for commercial use or not, please contact Gustavo Thomas at gustavothomastheatre@gmail.com.

Its stage hosts one company of Shanxi Opera, a regional style of Chinese Traditional Theater, offering scenes from this kind of Opera to hungry groups of Chinese turists. (It will be the subject of other posts)

There are, inside the Tea House Theater complex, and surrounded by traditional gardens, one long wall with clay made murals, in high reliefs o "altorelieve", showing scenes from Shanxi opera plays. Even the artistic work is not fantastic it is an interesting experience.

The amount of artistic depictions of theater artists and scenes of plays in China is comparable to the amount of religious images in temples or political scenes in palaces, that is something I have never seen in other part of the world. The social importance of theater before the Communist era was really remarcable, and these murals are a prove of it.

Video: Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater

Shanxi Opera Clay Murals at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

http://gustavothomastheatre.blogspot.com/2008/11/pingyao-tea-house-theater-shanxi-opera.html

Pingyao Tea House Theatre is one of some well preserved (and rebuilt) theatres inside Pingyao Ancient City in Shanxi province. It has many clay murals depicting scenes from Shanxi Opera

Shanxi Opera Clay Murals at Pingyao Tea House Theatre from Gustavo Thomas on Vimeo.

http://gustavothomastheatre.blogspot.com/2008/11/pingyao-tea-house-theater-shanxi-opera.html

Pingyao Tea House Theatre is one of some well preserved (and rebuilt) theatres inside Pingyao Ancient City in Shanxi province. It has many clay murals depicting scenes from Shanxi Opera

Photographs: Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008) Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008) Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008) Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008) Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)

Murals of Pingyao Tea House Theater. (July 2008)Texts, photographs and videos in this Blog are all author's property, except when marked. All rights reserved by Gustavo Thomas. If you have any interest in using any text, photograph or video from this Blog, for commercial use or not, please contact Gustavo Thomas at gustavothomastheatre@gmail.com.

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Mei Lanfang Grand Theatre in Beijing, China.

In November 2007 the Mei Lanfang Grand Theatre (1) was opened to the public, just a few meters from the so called Financial Street, where Chinese richest financial institutions have their luxurious offices, surrounded by not less luxurious hotels and fantastic malls.

During the day the theatre building seems a simple steel structure with enormous windows, only differentiated from other buildings around by a very shiny wall painted in red with decorative motives in gold (probably only plastic), Chinese preferred colours. But the same theatre at night, with lights inside and outside the building, changes up to turning in a futuristic comic space shift-style building.

During the day the theatre building seems a simple steel structure with enormous windows, only differentiated from other buildings around by a very shiny wall painted in red with decorative motives in gold (probably only plastic), Chinese preferred colours. But the same theatre at night, with lights inside and outside the building, changes up to turning in a futuristic comic space shift-style building.

The Theatre is not specialized in Peking Opera only, it hosts many kind of operas from all over China and also Western-style musicals. That evening I saw an opera called "Zouxikou" 走西口 from Shanxi province. Nothing special for me; kind of traditional masses performance played in the worst realistic style. I took some photographs that illustrate my lack of comment about it. (See the Spanish version of this Blog)

.

(1) A rare event, Chinese theatres usually have names coming from the area they are located or some nice sentences from litetature or poetry; a individual's name means that the man is very very important, as Mei Lanfang is.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

In Anton’s Garden. The letters from Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper.

"Who envelops you, beautiful Anton?"

More than 15 years ago I wondered about the mystery of his person and his writing, and at the same time I wrote:

¿Quién te envuelve, bello Antón?

Tu misterio se escribe en la cara.

Tus lentes, reflejo ríspido de soledad;

de ambición desmedida por la nada.

(Who envelops you, beautiful Anton?

Your mystery is written on your face.

Your glasses, rough reflection of loneliness;

of unbridled ambition for nothingness.)

I continuously looked at the only photo available in those times of no internet, I observed it trying to discover its hidden secrets behind the colourless image; his life came to my in small bits, all I knew about him were his theatre plays translated into Spanish.

Then I found some letters, very few short sentences about his life as a writer, advices for his brother, comments of his disgust towards certain freedoms the Moscow Art Theatre was taking with his plays.

And I kept coming back to that photo, and writing about it...

Sonrisa que no existe.

Monalisa rusa de color sepia.

Hombre-mujer. Impresión de pasividad.

(Smile that exists not.

Sepia coloured Russian Monalisa.

Woman-man. Impression of passivity. )

Yes, I didn’t see a sexual Chekhov, I didn’t seem him as open, or loving, or loved. He was just one image and chosen words for saying something; a strange combination of ideas superimposed on each other in my mind. And I still saw him as beautiful, him, the man.

¡Ay, bello Antón!

(Oh, beautiful Anton!)

And his plays...

Cada palabra desluce mis ironías;

tus diálogos desnudan mi alma,

su alma,

y la de los demás...

(Every word dulls my ironies;

your dialogues disrobe my soul,

his soul,

and that of the others...)

Cada palabra tuya espera,

se alarga en hermosos silencios;

cada palabra tuya también grita

si deseamos hacerla gritar.

(Each of your words waits,

elongates into beautiful silences;

each of your words also screams

if we want to make it scream.)

I was fascinated by the mystery, of course, of his work, of his secrets, of his immense fame. I ask myself, why, then, did I also see him as part of a failure?

¡Ay, Antón, que lloras y glorificas tu fracaso!

(Oh, Anton, you cry and glorify your failure!)

I knew of his repulse, of his continuous illness, of his remote life in a southern port of the then Russian empire.

I wrote poems dedicated to him and based on small stories and impressions from his work; little by little my reading repeated itself, his plays again and again, his stories again and again, his few letters once more; and when languages (English and French) made their appearance in my life, the different visions that translations into other languages bring to us, and with that the doors they open.

On December 2004 I decided to take a week to submerge myself completely in the French theatre of the moment; I had six apotheotical nights of theatrical performances, Le Cirque Antoine, three Peter Brook’s productions, Théâtre du Soleil and Arianne Mnouchkine, among others. I went to the theatre on the second floor of the Théâtre de Champs Élysées to watch, not without emotion, in a production directed by Peter Brook, Natasha Parry and Michel Piccoli, “Ta main dans la mienne”, a play based on the letters that Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper wrote to each other for 6 years.

“Lui : - Je prends votre main dans la mienne -

Elle : - C’est ainsi qu’il les a signées - ses lettres - ses lettres à Olga -

Lui : - 400 lettres. -

Elle : - 412 pour être exact - d’abord en amis -

Lui : - ensuite en amants -

Elle : - ensuite en mari et femme -

Lui : - une vie de passion en six courtes années -

Elle : - Il était écrivain -

Lui : - elle était actrice -

Elle : - et ils se sont rencontrés - comment se sont-ils rencontrés ? -

Lui : - J’ai oublié ! -

Elle : - C’était à une lecture - une lecture de La Mouette. Avril 1898 - tu t’en souviens?” (1)

More than 15 years ago I wondered about the mystery of his person and his writing, and at the same time I wrote:

¿Quién te envuelve, bello Antón?

Tu misterio se escribe en la cara.

Tus lentes, reflejo ríspido de soledad;

de ambición desmedida por la nada.

(Who envelops you, beautiful Anton?

Your mystery is written on your face.

Your glasses, rough reflection of loneliness;

of unbridled ambition for nothingness.)

I continuously looked at the only photo available in those times of no internet, I observed it trying to discover its hidden secrets behind the colourless image; his life came to my in small bits, all I knew about him were his theatre plays translated into Spanish.

Then I found some letters, very few short sentences about his life as a writer, advices for his brother, comments of his disgust towards certain freedoms the Moscow Art Theatre was taking with his plays.

And I kept coming back to that photo, and writing about it...

Sonrisa que no existe.

Monalisa rusa de color sepia.

Hombre-mujer. Impresión de pasividad.

(Smile that exists not.

Sepia coloured Russian Monalisa.

Woman-man. Impression of passivity. )

Yes, I didn’t see a sexual Chekhov, I didn’t seem him as open, or loving, or loved. He was just one image and chosen words for saying something; a strange combination of ideas superimposed on each other in my mind. And I still saw him as beautiful, him, the man.

¡Ay, bello Antón!

(Oh, beautiful Anton!)

And his plays...

Cada palabra desluce mis ironías;

tus diálogos desnudan mi alma,

su alma,

y la de los demás...

(Every word dulls my ironies;

your dialogues disrobe my soul,

his soul,

and that of the others...)

Cada palabra tuya espera,

se alarga en hermosos silencios;

cada palabra tuya también grita

si deseamos hacerla gritar.

(Each of your words waits,

elongates into beautiful silences;

each of your words also screams

if we want to make it scream.)

I was fascinated by the mystery, of course, of his work, of his secrets, of his immense fame. I ask myself, why, then, did I also see him as part of a failure?

¡Ay, Antón, que lloras y glorificas tu fracaso!

(Oh, Anton, you cry and glorify your failure!)

I knew of his repulse, of his continuous illness, of his remote life in a southern port of the then Russian empire.

I wrote poems dedicated to him and based on small stories and impressions from his work; little by little my reading repeated itself, his plays again and again, his stories again and again, his few letters once more; and when languages (English and French) made their appearance in my life, the different visions that translations into other languages bring to us, and with that the doors they open.

On December 2004 I decided to take a week to submerge myself completely in the French theatre of the moment; I had six apotheotical nights of theatrical performances, Le Cirque Antoine, three Peter Brook’s productions, Théâtre du Soleil and Arianne Mnouchkine, among others. I went to the theatre on the second floor of the Théâtre de Champs Élysées to watch, not without emotion, in a production directed by Peter Brook, Natasha Parry and Michel Piccoli, “Ta main dans la mienne”, a play based on the letters that Anton Chekhov and Olga Knipper wrote to each other for 6 years.

“Lui : - Je prends votre main dans la mienne -

Elle : - C’est ainsi qu’il les a signées - ses lettres - ses lettres à Olga -

Lui : - 400 lettres. -

Elle : - 412 pour être exact - d’abord en amis -

Lui : - ensuite en amants -

Elle : - ensuite en mari et femme -

Lui : - une vie de passion en six courtes années -

Elle : - Il était écrivain -

Lui : - elle était actrice -

Elle : - et ils se sont rencontrés - comment se sont-ils rencontrés ? -

Lui : - J’ai oublié ! -

Elle : - C’était à une lecture - une lecture de La Mouette. Avril 1898 - tu t’en souviens?” (1)

The play presented to me, for the first time, a Chekhov in love, almost passionate about a woman (that was a surprise for me, of course), it presented, too, a Chekhov as an ordinary man, talking with less “Chekhovian sense”, well, not completely. For some (apparently obvious) reason, it was decided that the play be spoken mostly in the past tense; that made it Chekhovian, that made me lose he recently found man, it was as if it were a Chekhov written by Chekhov. But that didn’t keep me from enjoying it tremendously.

Something else from this mise-en-scene by Brook remained in my memory, Chekhov was old, very old; Michel Piccoli could barely stand, he was a man of wasted voice, an old man, and when he played a young man he seemed like an old man trying to feel youthful; Natasha Parry was also an older woman but, once you forgot her beautiful wrinkles, when she expressed her love, her adoring of the great author, with great subtleness, you forgot everything, she was Olga Knipper, who reminisced about those letters in her memories.

Something else from this mise-en-scene by Brook remained in my memory, Chekhov was old, very old; Michel Piccoli could barely stand, he was a man of wasted voice, an old man, and when he played a young man he seemed like an old man trying to feel youthful; Natasha Parry was also an older woman but, once you forgot her beautiful wrinkles, when she expressed her love, her adoring of the great author, with great subtleness, you forgot everything, she was Olga Knipper, who reminisced about those letters in her memories.Anton Chekhov was then split into two in my memory’s image: a photo of a young man, maybe mature, with an air of loneliness and simplicity; and an acting of an old, live, loving man, who I’d seen die on stage.

An old Chekhov...?

In 2007, when retaking the text of the acting method of Antonio González Caballero, with all that part devoted to the naturalist current of modern acting proposed by Chekhov, I had to go back to the artist and the man, and to delve more deeply I ordered two books, “The Moscow Art Theatre Letters” and “Dear writer Dear Actress” (2), both compilations by Jean Benedetti. It was (as it remains) also the era of the flood of information and images that internet provides.

The book about the letter from the Moscow Art Theatre didn’t but corroborate my opinions and information about the opinion Chekhov had of his plays and of Stanislavsky himself, but it was “Dear Writer Dear Actress” which, along with the letters exchanged between Chekhov and Olga Knipper, that created a revolution in my perception of the man that wrote one the the most important groups of plays belonging to the universal theatre.

Having turned forty, I would wake up almost before dawn with a strange feeling of apparently endless youth; confused, I’d look at myself in the mirror and was surprised by what nature, genetics and exercise maintained in my body and face; that was the time I read that Chekhov felt old at the same age... at forty, at my forty... Ill with tuberculosis he saw life leave while love arrived with all its power; locked in a boring, uneducated and lonely Yalta, his writings enjoyed a success he himself simply could not enjoy.

Only irony saved his mind.

“My little doggie” (“¡Mi perrita!”, how rude that sounds in Spanish!) was how he called, amongst dozens of other ridicule pet names, Olga Knipper, his beloved wife. In a 6 year-long love they met just a few times, and I strongly believe that that’s what kept their love alive while it lasted. Little sex, yes, but intense when it happened, sex that left them expecting a son, miscarried, who was supposed to be called Pamphil.

Letters upon letters show us how strange it was to depend on mail in those times; between Yalta, Moscow and Saint Petersburg, between Nice, Naples and Rome. Letters that arrive weeks late, some that arrive earlier than others, answers to others from weeks before...

-Why haven’t you written?-

-But I’ve sent you letters twice a day!-,

-Don’t be sad.-,

-I’m not sad, I wrote that in a different letter; now I’m happy-,

-I hear you’re ill-,

-I don’t have any health problems now-,

-Don’t send letters to Rome, send them to Naples; I haven’t been able to receive any from you.-

... A wonderful world of sentimental misunderstandings that never become a vaudevil, as it doesn’t happen either in his “comedies”.

Letters that presented a delicious Chekhov that washes little, that washes his hair even less, but who changes clothes somewhat more often; who enjoys a friendly dog until the dog prefers to sleep in his mother’s room. Chekhov, the man, lives the strange and tragic love of a young man that lives like an old one, who can’t go up the stairs, who suffers from colds, indigestion, continuous diarrhea, and an actress wife who parties and miscarries his son. A man who loves flowers, who devotes himself to a garden that sometimes goes crazy with tropical flair and other times remains as boring and dry as his neighbours in Yalta.

Those letters showed me also a Chekhov friend, worried for the health of Tolstoy and for the folkloric shirts of Gorky, for the lack of talent of his dear Nemirovich Danchenko and his wife’s worries; he is a man that dreams with a dacha near Moscow and with enjoying the silly and intellectual nights of a big city. Chekhov is a man of national fame but completely ignored internationally, who can travel through Europe and go to the theatre and not be recognised by anybody; he jokes with his wife for her being an actress that, thanks to a soon-to-be contract, would become as famous as Sarah Bernhardt.

Chekhov in his letters is a forgotten man in a small and remote world, old, sick, a smiling and ironical man that takes pleasure in seeing how people live while his wife reads or sings at his side. A man who constantly loses faith in his writing and suddenly becomes big with confidence once he finishes a play.

Chekhov, from what I read and I can read, was a man who, when he died, said a sentence in German and had a bit of champagne...

*

And today, watching his photograph again, I can write:

En el jardín de Antón

¿Quién te envuelve, bello Antón?

Tu misterio se escribe en tu cara.

Tus lentes, reflejo ríspido de soledad;

de ambición desmedida por la nada.

Sonrisa que no existe,

como una Monalisa rusa de color sepia.

Eres un hombre-mujer,

impresión de eterna pasividad.

¡Ay, bello Antón!

Cada una de tus palabras desluce mis ironías.

Tus diálogos desnudan mi alma,

su alma,

y el alma de los demás.

Cada una de tus palabras espera,

se alarga en hermosos silencios.

Si queremos las hacemos gritar.

Grita diciendo uno o dos...

¡Ay, Antón que lloras y glorificas al fracaso!

¡Revolucionario de 40 años que a nadie mató!

In Anton’s Garden

Who envelops you, beautiful Anton?

Your mystery is written on your face.

Your glasses, rough reflection of loneliness;

of unbridled ambition for nothingness.

Smile that exists not.

Sepia coloured as Russian Monalisa.

You’re a woman-man,

Impression of eternal passivity.

Oh, beautiful Anton!

Every word dulls my ironies;

your dialogues disrobe my soul,

his soul,

and that of the others...

Each of your words waits,

elongates into beautiful silences;

if we want we make it scream.

Scream saying one or two...

Oh, Anton, you cry to and glorify failure!

40 year revolutionary who nobody killed!

(1) Original text of "Ta main dans la mienne"

(2) “Dear Writer Dear Actress” The Love letters of Anton Chekhov & Olga Knipper. Selected, edited and translated by Jean Benedetti. Methuen. U.K. 2007.

Friday, October 24, 2008

Strindberg photographer

Strindberg walked his life researching, he found similitudes and coincidences between matter and energy, he wondered about others' discoveries in fields like psychology, occultism and natural science. August Strindberg, a poet, a scientist, a thaumaturg, ill with an obsessive desire for being recognized as a renovator and a sage; in his obsession he penetrate secrets of many disciplines; he was an erudite but also had terrible mistakes, he was considered by many as pernicious and suffered humiliation; the prototype of a genius, he was only capable of recognizing his own reality and truth.

Walking through his marvelous life he talked about Bohemia, in which he found flowers which seemed images he recognized from his photographic plates; he observed streams of water similar to chemical products he worked with; he perceived above the wind the light from which everything comes from; he intended to penetrate bodies and discover their real interior.

“Je sais très bien que les psychologues ont inventé un vilain nom grec pour définir la tendance à voir des analogies partout, mais cela ne m’effraie guère, car je sais qu’il y a des ressemblances partout, attendu que tout est en tout, partout”. (Inferno) (1)

If we try to understand his genius only through his theatrical career, then we will miss an enormous field of precious information.

Strindberg was also an alchemist who looked for the origins of objects, throughout an internalization process he worked with substances to penetrate any matter and discover its secrets. Strindberg the photographer used photography as a ”medium”, chemical combinations didn’t work, so images, photographic plates, experiments with light, could do the job then. He photographed his face, his rooms, his family, he tried to find the soul in the portrait with a special technique.

“J’ai préparé dans ma tête une histoire qui contient le maximum d’humeurs differentes. Je me raconte l’histoire tout en exposant la plaque et en regardant fixement la victime. sans suspecter ce que la force à faire, sous l’influence de la suggestion, il est obligé de réagir à ces influences qui le pénètrent. Et la plaque fixe l’expression de son visage. Le tout dure exactament trente secondes - mon histoire est minutieusement calculée pour cette durée. En trente secondes j’ai capté le sujet dans sa totalité!” (Quoted by Per Hemmingson)

Strindberg photographed the sky, the clouds, the stars; he used to leave his plates during the night under the effect of the moonlight and the next morning came back to look for changes and tried to explain what he saw there: images of the night, images of what we are not able to see with our eyes, images of the invisible. He subscribed to the crazy idea of extracting part of the soul of others through photography (what other thing could a photographic image be but part of the soul?). He trusted in X Rays as a philosophical way of understanding matter and energy. He detested the delusion of our eyes but he was amazed by them and he used to penetrate that delusion and imagined stories; gelatin plates were a field of illusion, a way of wonders.

“Je suis retourné à mes formations de cristaux que je photographie directement en les copiant de la plaque de verre où la cristallisation se trouve. Ces agrégats, des fleurs de glace, m’ont ouvert des perspectives dans les secrets de la nature qui me stupéfiaient” (Quoted by Per Hemmingson)

My heart always breaks when reading his honest letters, his petitions, his explanations and his furious claims over the incomprehension of others; I have also cried watching his photographs of dark skies and clouds over Stockholm.

As for the soul, when Strindberg discovered psychology, he called it “the unconscious”, and during his long walk of life he bases his research on the supra-natural; having rolled in the sick pleasures of realism and naturalism, his hunger for more pleasure led him to look even deeper or more downward or more inward; later “the others” would call it surrealism: supra-natural was his word.

“C’est donc à moi de jeter la pasarelle entre le naturalisme et le supranaturalisme en proclamant que celui-ci ne constitue qu’un devéloppement de celui’la” (Quoted by Eric Renner)

When he came upon camera theatre where, through actions and words he exposed the world of the soul, of the supra-natural, of the unconscious, the road had been already been traversed by the avatars of exploration; his theatre was and (still is) revolutionary because it came to him as an inevitable result of those failed encounter with alchemy, astronomy, science, philosophy and photography.

“Je cherche la vérité dans la photographie, intensément, comme je la cherche dans beaucoup d’autres domaines.” (Inferno)

Today more than ever I’m fully convinced that to know (and to enjoy even more) Strindberg’s work we have to see and read his “images”.

*

I received, as a birthday gift from someone who loves me, a small book edited in 1994 by Actes Sud, “L’expérience Photographique d’August Strindberg”, written by Clément Chéroux, with a delicious “anexo” including some short extracts from texts written by Strindberg himself about his photographic experience. At the beginning the book seemed to me a little bit conventional, but when I started to read and to feel Strindberg’s powerful experiences with Photography and his research, those words caused real admiration for Chéroux’s work to awake in me.

I received, as a birthday gift from someone who loves me, a small book edited in 1994 by Actes Sud, “L’expérience Photographique d’August Strindberg”, written by Clément Chéroux, with a delicious “anexo” including some short extracts from texts written by Strindberg himself about his photographic experience. At the beginning the book seemed to me a little bit conventional, but when I started to read and to feel Strindberg’s powerful experiences with Photography and his research, those words caused real admiration for Chéroux’s work to awake in me.Now I can understand why, some years later, and after the book was published, The National Stockholm Museum and Le Musée d’Orsay exhibited a large part of Strindberg’s photographic and painting work (2), without any preamble to his literary and theatrical work but as a unique painter and photographer.

(1) I’ve decided not to translate those texts ( some are translations from Swedish to French themselves) because I thought I could make terrible mistakes trying to put Strindberg’s ideas in English (or Spanish). I’m sure there are some versions of this texts in your language.

(2) The exhibition was mainly known thanks to the book that was published about it: “August Strindberg Painter and Photographer”, edited by Yale University and Stockholm Museum.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)